July 11, 2021

Having roamed the Earth for around 200 million years — including through the last mass extinction event — turtles appear to have evolution and survival on their side.

But turtles now face unprecedented challenges in the familiar tunes of habitat loss, human encroachment and overexploitation. They are one of the most threatened taxa on the planet, with about 60% of all turtle and tortoise species at risk of extinction.

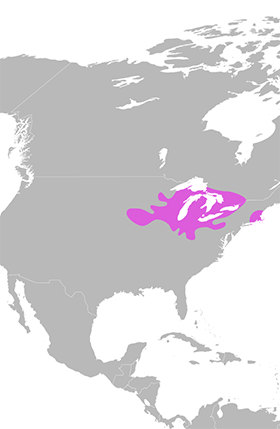

Unfortunately, the story is the same for the Blanding’s turtle, a freshwater turtle native to the Great Lakes states, parts of central and eastern U.S. and southeast Canada. Recently petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act, the Blanding’s turtle is considered threatened in Ohio and threatened, endangered or a species of concern in all but one of the 15 states where they occur.

Bearing distinctive yellow necks, “Blanding’s turtles always look like they’re smiling,” said Matt Cross, a conservation biologist at the Toledo Zoo who’s been working on a project funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to assess the status of Blanding’s turtles in Ohio and Michigan. The project, which includes individuals from the Toledo Zoo, the Ohio Biodiversity Conservation Partnership, the Ohio Division of Wildlife and Michigan Natural Features Inventory, will result in a comprehensive conservation plan for the species.

“Before this project, the very basic questions of where these turtles are and how the populations are doing were unanswered for most of Michigan and Ohio,” Cross said. “We knew wetland loss was a big issue — Ohio, for example, has lost 92% of its historical wetlands — but this work has allowed us to determine regional Blanding’s turtle presence and what habitats need protected or restored.” Watch Matt Cross’s OWMA Conference presentation about Blanding’s turtles >>

Since 2019, the team has implemented population monitoring and modeling, identified habitat priority areas, analyzed turtle genetics and begun efforts to rear Blanding’s turtle eggs in captivity so they can be released back into the wild. Cross’s group has also been tracking around 25 Blanding’s turtles using radio transmitters, which has clued researchers into turtles’ movement corridors and where they’re choosing to nest and hibernate.

“A lot of times they’re nesting or overwintering in risky areas like agricultural fields or ditches that end up being dredged,” said Cross, noting solutions could include signage, crossing culverts and artificial nesting beaches.

Lastly, the Blanding’s turtle project mobilized citizen scientists to help monitor Blanding’s turtles in suburban areas, where eggs face many threats from neighborhood wildlife and human activity, Cross said. One citizen scientist, Terry Breymaier, became so involved that researchers helped him get a permit to handle the turtles, which is otherwise prohibited. He even earned a spot as co-author on a publication about the work.

Bill Peterman, a wildlife ecology professor at The Ohio State University and expert on amphibians and reptiles who was not involved in the project, applauded the team’s efforts to engage citizen science.

“People are interested in amphibians and reptiles, but we don’t have these massive public databases of records and trends like we do with birds,” Peterman said. “Anything we can learn about our populations now is essential to conservation in the future.”

The future of Blanding’s turtles

Blanding’s turtles won’t have an easy road to recovery, especially considering it takes 15 years for females to reach reproductive age and most offspring never make it to adulthood. This dynamic sometimes creates what Cross calls a “ghost population,” which appears to be healthy but is not actively replacing itself because no individuals are reproducing. In addition, landscape alteration and fragmentation pose a consistent threat to turtles, Peterman said.

“Most of our freshwater turtle species at some point in their life are going to be crossing land, whether that’s males looking for mates or females looking for nesting sites,” Peterman said. “If females successfully find a place to nest, because of how we’ve modified the landscape, we often have large populations of meso-predators like raccoons or skunks. Without active protection of nests or removal of predators or both, nest success can be almost nonexistent.”

Despite hurdles ahead, Cross said he envisions a brighter future for Blanding’s turtles.

“Blanding’s turtles are cute — they’re a great ambassador for turtles, wetlands and conservation issues,” he said. “Making sure they stick around for future generations is a pretty good idea.”

Ohioans can help Blanding’s turtles by:

– Being mindful when driving

– Reporting sightings via HerpMapper (similar to iNaturalist), https://www.toledozoo.org/conservation, turtles@toledozoo.org or 419-385-5721 x 2156

– Creating or maintaining wetland habitat on your property, with advice from an Ohio private lands biologist or help from programs like H2Ohio or USDA Wetland Reserve Easements